In Honour Of Made Up Stuff

I learned my tai chi form about 25 years ago. I stopped going to the class where I learned it about 15 years ago. Since then, my practice has been largely solo, although I’ve taught tai chi to other people and occasionally visited my teacher to get corrections and feedback.

About two years ago, my instructor looked at my form and told me I was doing one of the moves wrong. I won’t say which move it is. It’s not important. What is important is that I responded by reminding him of the instructions and interpretations he had always given while teaching the move.

He said, yes, but his own teacher had subsequently corrected him on the matter. I replied, hmm, but I am sure I remember him explaining what the application of the move was and hence the sequence of the different stages of the move and the correct weighting distribution, and so on.

My teacher said, yes, he remembered all of that as well, but that nonetheless, I was now doing it wrong. We spent the rest of the session trying to correct my two decades long ‘mistake’.

Since that time, I have decided I will not try to correct the movement. This means that every time I reach that point in the form, I think ‘oh, this bit is wrong’, and carry on.

I leave the move ‘uncorrected’ to honour the made-up-ness of this and all tai chi forms, and by extension of everything in all martial arts and pretty much everything else in life too.

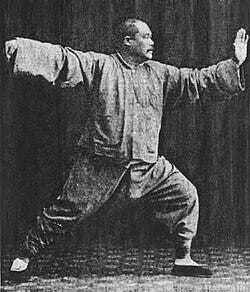

My tai chi form was made up. And not thousands of years ago on a misty mountain by a Daoist Immortal. Probably in the late 1980s, when increased popularity in tai chi meant that a lot of instructors shortened their long forms in order to provide more rapid customer satisfaction.

Before that, forms were standardized and shortened in by the Chinese state, when they were implemented in educational institutions. They have been modified for display. Diasporic Chinese family regional forms have drifted in style and execution. Individual teachers have made tweaks and alterations. And so the story goes.

The way I now look at it, all of this stuff is made up, so I now honour and celebrate the brilliance of different kinds of invention and modification.

While I have not had the confidence to modify my own tai chi form myself, I have no qualms about altering a lot of accessory training movements. For instance, the baduanjin – 8 stretches that are like a kind of standing yoga. My own teacher was taught by a teacher who was taught my Master Lam Kam Chuen. So, my baduanjin must be the same as his, right? Wrong. Master Lam once had a British TV series called Stand Still, Be Fit, which aired on Channel 4. In that series, he teaches the baduanjin. And it’s completely different from ‘my’ baduanjin. Weird.

So, now, I interrogate every stretch/relax sequence, every element, and make decisions. Is this stretch as good as it can be for me? Can I tweak things? The answer is sometimes no, and sometimes yes. So I make changes or I don’t, determined by the day, determined by whether and where I might ache or not, the weather, whether it’s warm or cold, whether I am tired or energetic, relaxed or stressed, and so on.

And that’s it, and that’s the point. Yes, I encounter a twang of guilt that I have not learned the new ‘correct’ way to do that move. But now I just reflect on the reasons for that guilt and on the contingency of the sequence as a mobile and dynamic social construct, and on our strange fetishistic tendency to want to reify something made up into something supposedly sacred and unchanging. Even though things do nothing but change.

Comments

Post a Comment