Multicultural Exercise and Cultural Colonialism

1. Multicultural Functional Fitness

In gym and exercise circles, the kettlebell craze of the early 2000s fuelled the emergence of ‘functional fitness’. Functional fitness rejects both the bodybuilding ethos of hypertrophy for hypertrophy’s sake and the aerobics focus on endurance alone. It privileges instead complex athletic movements, endurance with resistance or under load, mobility and, well, ‘functionality’.

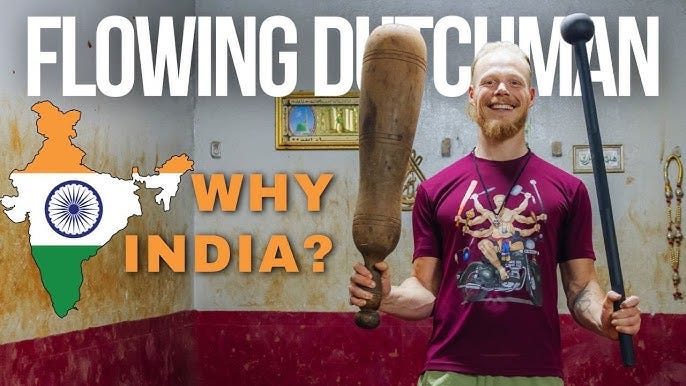

The 21st century Western interest in functional fitness has precipitated a reappraising of pre-bodybuilding and often non-Western exercise tools. Among these are the full range of ‘Indian clubs’ – maces, gadas, joris, pairs of clubs of all shapes and sizes, as well as the newer heavy steel clubs.

A popular proponent of mace, gada and club swinging is Harbert Eggert, aka, The Flowing Dutchman, whose performances with clubs and maces in Amsterdam led to a large social media following. He has capitalised on this with evermore video-recorded trips East over recent years, in which he makes pilgrimages to the fonts and sources of many traditions, visiting wrestling akharas and kalaripayattu clubs all over India. These are videoed, edited, and posted on his various channels.

Back home, Eggert has established the Dutch Flow Academy, with physical and online incarnations, in which he trains and accredits people as instructors in various styles of Indian clubs.

2. Extractivism

In ethnography and anthropology, ‘extractivism’ refers to exploitative practices in which researchers extract knowledge, stories, or data from communities without meaningful reciprocity. Methodologically and ethically, this is regarded by contemporary academics as being akin to resource plundering in colonial economies.

Anthropologists critique extractivism as a metaphorical extension of raw material extraction, involving asymmetrical power flows that prioritize Western gain over non-Western participants’ needs or benefits. It is regarded as mirroring or echoing colonial capitalist exploitation, as field sites become ‘mines’ for data to be ‘harvested’, unidirectionally.

Scholars critique any ethnography that takes advantage of studied communities through one-way knowledge flows. Of course, extractivism differs from direct economic ‘extraction’, but it repeats non-reciprocal power and economic dynamics. In some cases, it is regarded as leading to forms of standardisation, homogenisation or cultural conflation that renders specific and precise local knowledges both interchangeable and exchangeable globally while erasing singularities and particularities.

3. Dutch Flows

If we immerse ourselves in the social media output of the Dutch Eggert (The Flowing Dutchman), it might be possible to suspect that this should not really be connected with extractivism. Indeed, his approach arguably demonstrates several counter-extractivist practices.

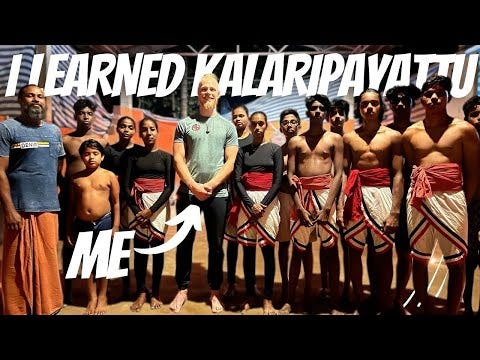

The Flowing Dutchman’s video content emphasizes two-way engagement rather than unidirectional data extraction. He documents practices of mace and club training traditions and styles from India and other cultures, and he clearly frames this within a broader commitment to community participation and skill-sharing. He films himself with Indian experts embedded within their training cultures.

His documentary work may seem aligned with a decolonial ethos of participatory knowledge production, rather than extractive research. He clearly collaborates with the practitioners he encounters, and his films show shared passion and community atmosphere. His discussions reveal his focus on how people transform their lives through engagement with the work, positioning participants as agents rather than passive data sources.

Also, Eggert explicitly acknowledges the history and cultural contexts of the tools he teaches (particularly Indian gada/mace traditions), documenting his own learning journey rather than appropriating knowledge without attribution. This contrasts with extractivist knowledge practices that decontextualize and commodify local practices without recognition.

However, his work clearly operates within commercial structures – the world of paid courses, certifications, coaching, merch, etc. This kind of commodification of knowledge, even if shared reciprocally, raises some questions. There is a sharp distinction between collaborative knowledge production and independent or individual knowledge monetization. This is particularly notable given the non-Western sources of the practices he studies and integrates.

Accordingly, the relationship between documentation (his documentary projects) and the practitioners he’s engaging with should be assessed in terms of whether those communities 1) have agency over their representation and 2) receive any financial benefits from the distribution of their images and performances.

3. Epistemic Extractivism

These latter considerations point to what anthropological critique would call ‘epistemic extractivism’. This is a more subtle form of knowledge appropriation that operates through authority consolidation rather than simple data/material theft.

After visiting India, Eggert returns to Amsterdam and effectively positions himself as an ‘expert’ and ‘master’ of mace practice, trading on his ‘authentic’ experiences and first-hand knowledge with Indian practices, while abroad. On this basis, his Academy certificates ‘Master Mace Instructors’. As such, the Flowing Dutchman enacts a classic extractivist manoeuvre: having harvested knowledge from dispersed, non-Western practitioners (Indian gada traditions, traditional club work), he synthesizes it through his own pedagogical apparatus and then re-distributes it under his branded institutional authority (Dutch Flow Academy). The knowledge becomes ‘his’ system, his certification, his expertise.

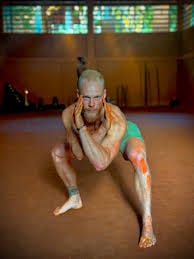

Moreover, even before this, we can see that in his ‘community’ and ‘pilgrimage’ style videos, he centralizes himself in the video output. What is primarily held up for our inspection and admiration is him – his body in action. We often see Eggert performing with extremely heavy gadas and other clubs, to the delight and amazement of his Indian audience.

This may be aligned with various problematic mechanisms, from Eurocentric cultural extractivism to mandatory entrepreneurial ‘Instagrift’, and more. Nonetheless, by constantly appearing as the star of the show, often as (the most?) impressive performer, often as authoritative instructor, often as guide and interpreter, he establishes himself as the epistemic gatekeeper.

The communities and practitioners from which knowledge originates become sidelined or comparatively silenced sources. Viewers encounter foreign knowledge through his mediation and framing. This mirrors what contemporary scholarship identifies as ‘scientific extractivism’, or what Edward Said regarded as the exemplary operation of orientalism: the collection of Eastern knowledge and its installation and institutionalisation in the West.

Comments

Post a Comment